Join the UKTC’s mailing list to be notified about our conferences and events, and new resources.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and Complex PTSD

PTSD is the diagnostic label used to describe a particular profile of symptoms that people sometimes develop after experiencing or witnessing a potentially traumatic event or events.

PTSD does not describe the full range of reactions to traumatic events; there will be many children and young people who are ‘traumatised’ by events, but their particular difficulties will not fulfil the criteria for PTSD.

What is a diagnosis?

A diagnosis is a formal label that describes a certain set of problems or symptoms. Official diagnostic criteria describe which symptoms are necessary for any particular diagnosis. A diagnosis should help the person experiencing symptoms and should always be used in the context of a wider understanding of the person’s needs, challenges and strengths when developing care plans. In mental health, diagnoses often describe a group of shared thoughts, behaviours and symptoms. Identifying these groupings helps professionals communicate effectively and, more importantly, supports research to identify what works to help people experiencing difficulties.

In some cases, a person’s particular profile of difficulties may not meet the threshold for a diagnosis, but they can still be very distressing and warrant treatment.

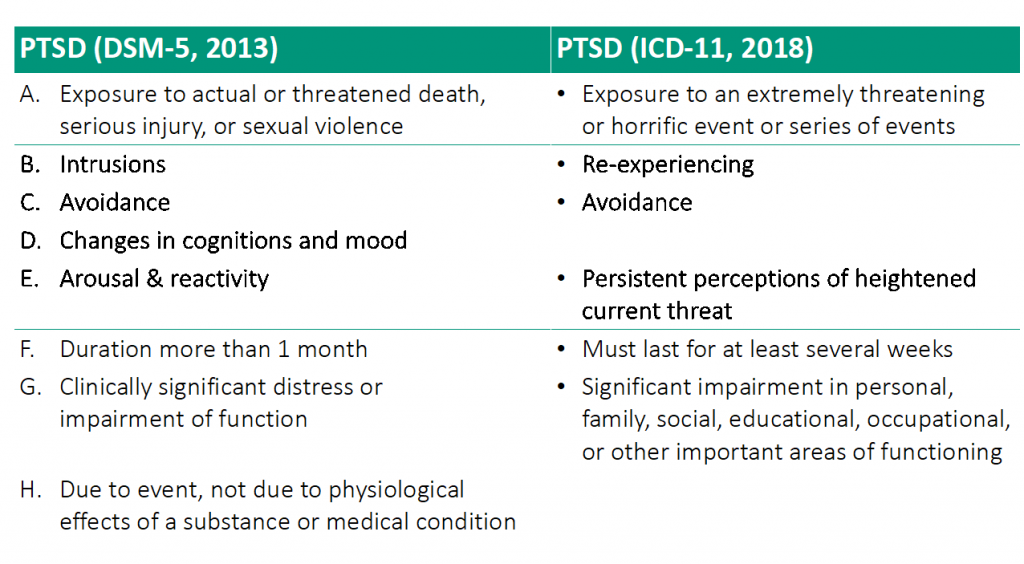

There are two similar but not identical, recognised sets of diagnostic criteria for mental health problems:

- The International Classification of Diseases – 11th Revision (ICD-11) produced by the World Health Organisation (WHO)[1].

- The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual – 5th Edition (DSM-5) produced by the American Psychiatric Association (APA)[2].

People find different kinds of meaning in diagnosis. For some people it helps them explain or make sense of the experiences they have had and the impact it has had on their lives. For others it may feel stigmatising, reductive, meaningless or result in them feeling like they are being treated as a set of symptoms rather than a person.

What is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)?

PTSD was first officially defined in 1980 when the APA published the 3rd edition of its diagnostic classification system the DSM-III. The actual criteria have changed a bit over time.

According to the DSM-5, in order to fulfil the criteria for a diagnosis of PTSD, the person must have experienced or witnessed a traumatic event that involved “actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence”. Whereas according to the ICD-11, the event or events must have been “extremely threatening or horrific”.

It is worth noting here that there are events that might not meet these particular criteria, but which may nevertheless be traumatic for the child or young person and may lead to the symptoms of PTSD described below, or to other significant mental health difficulties.

There are three groups of symptoms that are common to both the ICD-11 and the DSM-5 criteria. These are sometimes considered to be the core symptoms of PTSD:

- Intrusions or re-experiencing of the event (such as intrusive memories, repetitive play in which the events or aspects of it are expressed, nightmares, flashbacks, distress triggered by reminders of the event or events).

- Avoidance (such as avoiding thoughts, feelings or memories of the event or events, or avoiding people, places, conversations or situations that are associated with the event or the events).

- Arousal and reactivity or sense of current threat (such as irritability, being overly vigilant, being easily startled, concentration problems, sleep problems).

The DSM-5 has taken a much broader approach and lists many more symptoms from each of the three groups above as well as including an additional set of symptoms related to changes in thoughts and feelings, such as:

- Exaggerated negative beliefs about themselves, the world or other people;

- Having distorted thoughts about what caused the event or events and the consequences;

- Persistent negative emotions;

- Less interest in significant events;

- Feeling detached or estranged from others and finding it impossible to experience positive emotions.

This broader array of symptoms increases the overlap with other mental health difficulties but allows for a wider range of symptom profiles to be classified as PTSD. Whereas the ICD-11 has taken a more restricted approach and focused on just two symptoms from each of the three core groups above. This may make assessment more straight-forward but may also lead to some children and young people who have less-common patterns of symptoms not receiving a diagnosis of PTSD [3].

Although the ICD-11 does not have the 4th group of symptoms related to changes in thoughts and feelings, it does have a separate diagnosis called Complex PTSD which is described in more detail below.

It is common for people to experience symptoms of PTSD in the days and weeks following a potentially traumatic event. But many of them will spontaneously recover, therefore PTSD cannot be diagnosed unless symptoms have persisted for a month (DSM-5), or several weeks (ICD-11).

Because the ICD-11 and DSM-5 are not the same, there will be some children and young people whose difficulties will fulfil one set of criteria but not the other. For example, several studies have found that following particular events, of those children and young people that have PTSD according to either the ICD-11 or the DSM-5, fewer than half fulfil both sets of criteria [4], [5]. This means that whether or not they can be diagnosed with PTSD depends on which set of criteria is being used.

Not all children who experience potentially traumatic events will develop PTSD. Research has found that between 5% and 67% of children and young people exposed to a potentially traumatic event actually develop PTSD; and that it is more likely if they have been exposed to interpersonal events (such as assault or abuse) rather than non-interpersonal ones (such as accidents or natural disasters) [6]. All of the following factors make it more likely that a child or young person will develop PTSD [7]:

- Thinking that they were going to die during the event

- Psychological difficulties before the traumatic events

- Stressful life events before the traumatic events

- Family difficulties after the events

- The carers having mental health problems after the events

- Lack of social support and social isolation after the events

We also know that children and young people from ethnic minorities are more likely to develop PTSD following a potentially traumatic event; however the reasons for this increased vulnerability are likely to be complex and require future systematic investigation.

What is Complex PTSD?

It has long been recognised that the reactions of some people following traumatic events extend beyond previous definitions of PTSD [8]. The DSM-5 took this into account with their wide approach as mentioned above. In contrast, the approach taken by ICD-11 was to formally define a new diagnosis of Complex PTSD. According to the ICD-11, Complex PTSD consists of the same core symptoms of (ICD-11) PTSD, but has three additional groups of symptoms (which are sometimes referred to as ‘disturbances in self-organisation’ or ‘DSO’):

- Problems in affect regulation (such as marked irritability or anger, feeling emotionally numb)

- Beliefs about oneself as diminished, defeated or worthless, accompanied by feelings of shame, guilt or failure related to the traumatic event

- Difficulties in sustaining relationships and in feeling close to others

Research has indicated that the diagnosis of Complex PTSD can apply to children and young people. In one study, of those taking part in a treatment trial for PTSD, 40% of them had high levels of the additional symptoms required for Complex PTSD [9].

What helps with PTSD and Complex PTSD?

There are two particular interventions that are generally recommended if a child or young person has a diagnosis of PTSD [10]: Trauma-focused Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (TF-CBT) and Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR). Research has consistently found that these are effective for PTSD in children and young people. However that does not mean that they will work for all children with PTSD and some research indicates that other approaches might also be effective [11].

There is much less research evidence about what interventions are effective for Complex PTSD, however there is emerging evidence that what works for PTSD is likely to be effective for Complex PTSD [9], but it may require more sessions and more focus on developing a trusting relationship [10].

References:

- https://icd.who.int/en

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub.

- Friedman, M. J. (2013). Finalizing PTSD in DSM‐5: Getting here from there and where to go next. Journal of traumatic stress, 26(5), 548-556.

- Danzi, B. A., & La Greca, A. M. (2016). DSM‐IV, DSM‐5, and ICD‐11: Identifying children with posttraumatic stress disorder after disasters. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 57(12), 1444-1452.

- Sachser, C., Berliner, L., Holt, T., Jensen, T., Jungbluth, N., Risch, E., … & Goldbeck, L. (2018). Comparing the dimensional structure and diagnostic algorithms between DSM-5 and ICD-11 PTSD in children and adolescents. European child & adolescent psychiatry, 27(2), 181-190.

- Alisic, E., Zalta, A. K., Van Wesel, F., Larsen, S. E., Hafstad, G. S., Hassanpour, K., & Smid, G. E. (2014). Rates of post-traumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed children and adolescents: meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 204(5), 335-340.

- Trickey, D., Siddaway, A. P., Meiser-Stedman, R., Serpell, L., & Field, A. P. (2012). A meta-analysis of risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Clinical psychology review, 32(2), 122-138.

- Herman, J. L. (1992). Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. Journal of traumatic stress, 5(3), 377-391.

- Sachser, C., Keller, F., & Goldbeck, L. (2017). Complex PTSD as proposed for ICD‐11: validation of a new disorder in children and adolescents and their response to Trauma‐Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(2), 160-168.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Post-traumatic stress disorder. NG116. 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/ guidance/ng116

- Mavranezouli, I., Megnin‐Viggars, O., Daly, C., Dias, S., Stockton, S., Meiser‐Stedman, R., … & Pilling, S. (2020). Research Review: Psychological and psychosocial treatments for children and young people with post‐traumatic stress disorder: a network meta‐analysis. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 61(1), 18-29.

Learn more

Download our free evidence based resources to help children and young people affected by war, migration and asylum as well as the professionals supporting them in both educational and community settings here.