Join the UKTC’s mailing list to be notified about our conferences and events, and new resources.

Trauma

Trauma refers to the way that some distressing events are so extreme or intense that they overwhelm a person’s ability to cope, resulting in lasting negative impact.

The sorts of events that traumatise people are usually beyond the person’s control [1]. This may include sexual or physical abuse or assaults, terrorist attacks, war, natural disasters, traffic collisions, serious accidents, fires, kidnap, death of a close friend or family member (especially if sudden and unexpected), and painful or frightening medical procedures. Racism and other forms of group hatred and/or discrimination can also result in a traumatic response, for more information please see our Racism, Mental Health and Trauma Research Round Up [2], [3]. Children and young people can be traumatised by such experiences if the events happen directly to them, or if they witness or learn about them happening to someone else.

The experience or witnessing of traumatic events does not explain the impact on the individual as there will be many factors that influence the immediate and long term consequences. These include the socio-cultural-political context. For example, when a natural disaster such as an earthquake occurs, the likelihood of the event being traumatic for those involved will be influenced by many factors such as the emergency service response, levels of poverty and overcrowding, building infrastructure and the political response to the disaster.

Experiencing or witnessing traumatic events in childhood can have particularly devastating consequences, and is associated with adaptations in brain structure and function and impact a child or young person’s cognitive, emotional and social development [4], [5], [6], [7]. We know that childhood trauma is associated with increased risk of later mental health problems, difficulties in personal and social relationships, as well as increased risk of new stressful experiences, including repeated abuse [8], [9], [10].

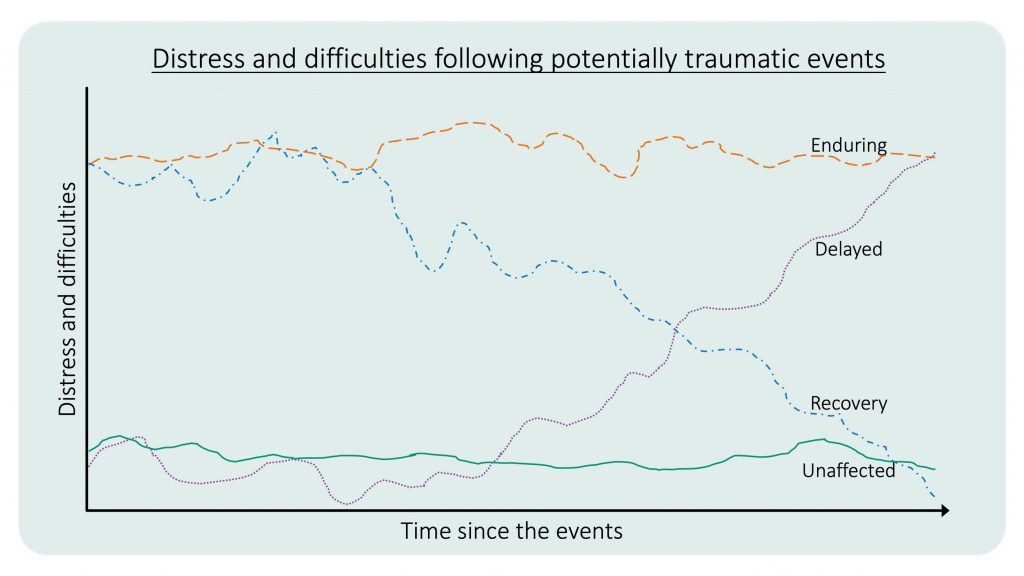

After experiencing or witnessing an extremely distressing event, many children and young people will initially experience high levels of distress and find it difficult to get on with their normal life. Most of those will spontaneously recover in the weeks and months that follow, while others will develop lasting difficulties. A minority of children and young people initially may experience very little reaction even to extreme events. But over a longer period of time, some of those seemingly unaffected children and young people may develop a range of difficulties. There are four different pathways or trajectories that have been identified – enduring, recovery, unaffected and delayed and these are set out in the graph below (adapted from Bonanno [11]).

The actual type of distress and difficulties that children and young people may experience after traumatic events can vary a great deal. Sometimes the difficulties experienced will fulfil criteria for a diagnosis of a mental health problem (e.g. anxiety disorders or major depression), and sometimes they will not.

Find more information on two diagnoses particularly associated with trauma on the Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Complex PTSD and Complex Trauma pages.

References:

- Eth, S., & Pynoos, R. (1984). Developmental perspectives on psychic trauma in childhood. In C. R. Figley (Ed.), Trauma and its wake. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

- Polanco-Roman, L., Danies, A., & Anglin, D. M. (2016). Racial discrimination as race-based trauma, coping strategies, and dissociative symptoms among emerging adults. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 8(5), 609.

- Comas-Díaz, L., Hall, G. N., & Neville, H. A. (2019). Racial trauma: Theory, research, and healing: Introduction to the special issue. American Psychologist, 74(1), 1.

- Gilbert, R., Widom, C. S., Browne, K., Fergusson, D., Webb, E., & Janson, S. (2009). Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. The Lancet, 373, 68–81. doi:10.1016/ S0140-6736(08)61706-7

- McCrory, E. J., Gerin, M. I., & Viding, E. (2017). Annual research review: childhood maltreatment, latent vulnerability and the shift to preventative psychiatry–the contribution of functional brain imaging. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 58(4), 338-357

- Mezzacappa E, Kindlon D, Earls F. (2001). Child abuse and performance task assessments of executive functions in boys. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 42(8), 1041- 1048.

- Danese, A., & McCrory, E. (2015). Child maltreatment. Rutter’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 364-375.

- Widom, C.S., Czaja, S.J., & Dutton, M.A. (2008). Childhood victimization and lifetime revictimization. Child Abuse and Neglect, 32, 785–796.

- Widom, C.S., Czaja, S., & Dutton, M.A. (2014). Child abuse and neglect and intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration: A prospective investigation. Child Abuse and Neglect, 38, 650–663.

- Gerin, M. I., Viding, E., Pingault, J. B., Puetz, V. B., Knodt, A. R., Radtke, S. R., … & McCrory, E. J. (2019). Heightened amygdala reactivity and increased stress generation predict internalizing symptoms in adults following childhood maltreatment. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 60(7), 752-761.

- Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American psychologist, 59(1), 20.