Join the UKTC’s mailing list to be notified about our conferences and events, and new resources.

Linking childhood trauma to mental health

In this video, Professor Eamon McCrory explains what scientists have learned about how childhood trauma puts children on a more risky path. However, many will go on to become resilient adults.

Watch the video

Video transcript

We know the children who have experienced abuse neglect are more at risk of later mental health problems. How can we understand this link? How does vulnerability affect a child’s everyday behaviour?

When a child grows up in an environment where there’s abuse and neglect, their brain is shaped by those experiences. These brain changes are unlikely to lead to an immediate diagnosable problem. They are also not brain damage. Rather, they may help the child survive in the short-term. But over time, these changes may make a child more vulnerable to mental health problems in the future. This unseen link between childhood trauma and later mental health problems is what we call latent vulnerability.

While latent vulnerability is a cause for concern, it does not determine anyone’s future. Brain changes aren’t fixed nor is the child’s destiny. While childhood trauma puts children on a more risky path, many children go on to become resilient adults.

Research tells us that mental health problems after abuse and neglect are not inevitable. Many children show a resilient outcome, yet a substantial number do not. Why are some children at more risk? Well, we know that a child doesn’t suddenly wake up one day with a mental health problem.

Well-being is created over time and maintained through our everyday experiences and our everyday relationships. These nurture our development and shape the way we think and feel about ourselves, other people, and the world around us. Stress susceptibility, stress generation, and social thinning are three pathways by which mental health problems may begin to develop slowly over time following abuse and neglect.

Stress Susceptibility (01:58)

Everyday challenges, such as taking an exam, moving to a new school or even making new friends can be stressful for anyone. However, for a child who has experienced abuse and neglect, they may find these situations even more difficult to manage. Scientists call this stress susceptibility.

Changes in the threat, reward, and memory systems can mean that everyday life takes a greater toll. Being on high alert, for example, may help a child stay safe in a threatening home environment, but it may not be so helpful at school or in a safe foster placement. Over time, it can lead to heightened stress responses in the body and may even affect the functioning of the immune system. Reduced response to reward and more focus on negative memories can make life feel more challenging and threatening.

Stress Generation (02:53)

It is really important not to think of brain changes as just happening inside the child. Mental health vulnerability can also arise because those same brain changes play out in the real world affecting a child’s future experience. In particular, their likelihood of experiencing future stress. While children who have experienced abuse and neglect have already experienced significant stress, we are learning that these same children continue to experience new stressful events more frequently than their peers. And we know that this happens even into adulthood.

For example we know that they are more likely to be bullied, more likely to experience relationship problems or exclusion. These are all examples of stress generation. Now why this happens is not straightforward. Scientists are working to understand what is likely to be a complex process involving a child’s genetic makeup, alterations in brain systems, and social behaviour. One possibility is that changes in the brain’s threat, reward, and memory systems may lead children to behave in ways that we as adults find challenging. Indeed how peers and adults respond to this behaviour influences whether new stressful experiences are created for the child.

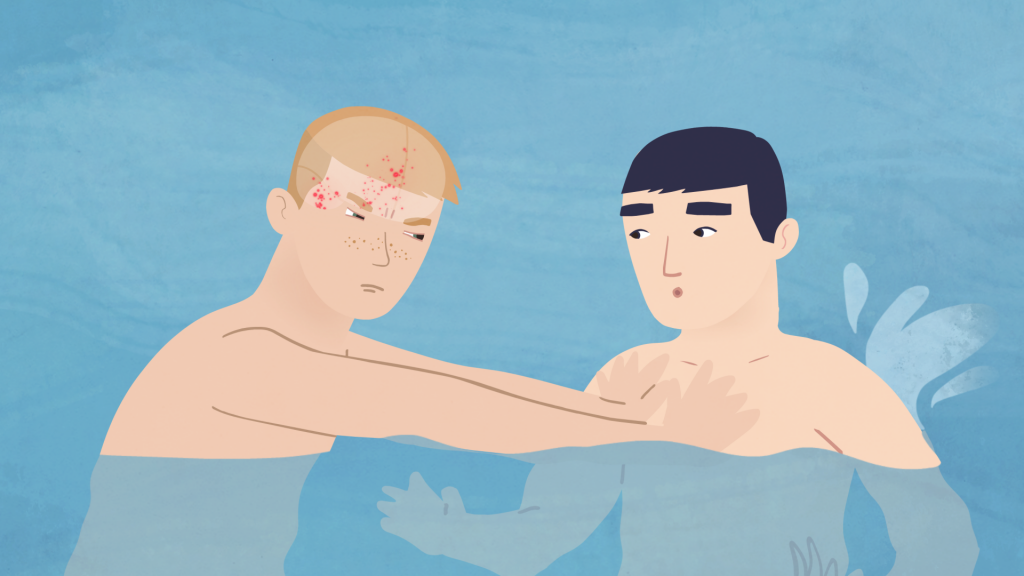

In the Childhood Trauma and the Brain animation, Jon overreacted in the pool and began to fight after what was just a friendly nudge. What happened next was not up to Jon, but up to his coach. She had a choice to make and the outcome of that choice determined whether Jon experienced a new stressful event or whether he had an opportunity for learning and development.

We know that experiencing stressful events increases anxiety and depression for all of us. If a child experiences more stressful events, it’s unsurprising that they are at a greater risk of mental health problems. It is possible that brain changes associated with abuse and neglect lead to brain changes that result in misinterpreting or overreacting to situations as well as poor social skills or difficulty regulating emotions. This can lead to behaviour that we, as adults, can find challenging. Our ability to step back and reflect and consider how to respond is crucial as we may, often with the best of intentions, be contributing to the generation of new stressful experiences for the children in our care.

Social Thinning (05:41)

Another way that we believe mental health vulnerability is linked to brain changes following abuse and neglect is through the impact these changes can have on everyday relationships. We know that supportive relationships are key to our well-being. They help us regulate our emotions and think through our everyday worries and problems. Adults also have an important role to play in creating opportunities for learning and growth for children.

Studies have shown that abuse and neglect in childhood can lead to reduced social support over time, even into adulthood. Conversely, it can lead them to develop relationships that are harmful and may lead to further experiences of victimisation. This has been recently been termed social thinning.

Over time, social thinning may make children more vulnerable to mental health problems. We all rely on others to manage stress and everyday challenges. Changes in the threat, reward, and memory systems may make it harder for children to build and maintain relationships. A child may focus on danger, on threat while missing out on other more positive social cues such as a friendly nudge or a positive remark. They may also be less able to draw on past experiences to solve current social problems or relationship conflicts. This may increase the risk of being excluded from a friendship group after an argument, being removed from a sports team after a fight, or being moved from a foster placement after sustained behavioural challenges.

While evidence points to social thinning for some children following abuse and neglect, how this contributes to mental health vulnerability is less clear. New stressful events may increase the likelihood of disrupting current relationships with peers or adults. At the same time, poor social problem solving may make it harder to resolve and repair social relationship difficulties. These difficulties can be compounded when it is harder to trust others.

Over time, through social thinning, a child may lose friends and relationships with supportive peers and adults. Reduced support from friends and family may make a child more vulnerable to the negative impact of new stressful events. If Jon had been excluded from the swim team, not only would he have lost the support of his peers, he would also have lost out on new experiences that could have helped him develop a sense of agency and a sense of confidence.

Conclusion (08:18)

So, we have seen that changes in the brain following abuse in neglect can not only affect how a child experiences the world, but also how the social world around them is shaped over time. This includes both their experience of new stressful events, as well as the social network of peers and adults around them.