Join the UKTC’s mailing list to be notified about our conferences and events, and new resources.

How the brain adapts to adversity

In this video, Professor Eamon McCrory uses Childhood Trauma and the Brain to help explain what scientists have discovered from studying the brain about the impact of abuse and neglect.

Watch the video

Video transcript

When children face traumatic experiences, like abuse and neglect, the brain can adapt to help them cope. These changes may be helpful in the short-term, in an unpredictable or dangerous home environment, but in the longer term, in more ordinary environments, these changes can play out in ways that increase risk of mental health problems. We call this latent vulnerability.

Neuroscientists have observed brain changes in a range of systems and here we’re going to focus on what we have learned about the threat, reward, and memory systems.

Threat system (0:48)

We probably know more about how experiences of abuse and neglect affect threat processing than any other brain system.

The threat system essentially allows us to detect and respond to danger. It helps us spot danger early in our environment and keep us safe — from a speeding car to avoiding a scary looking spider. These responses are a normal part of life for all of us.

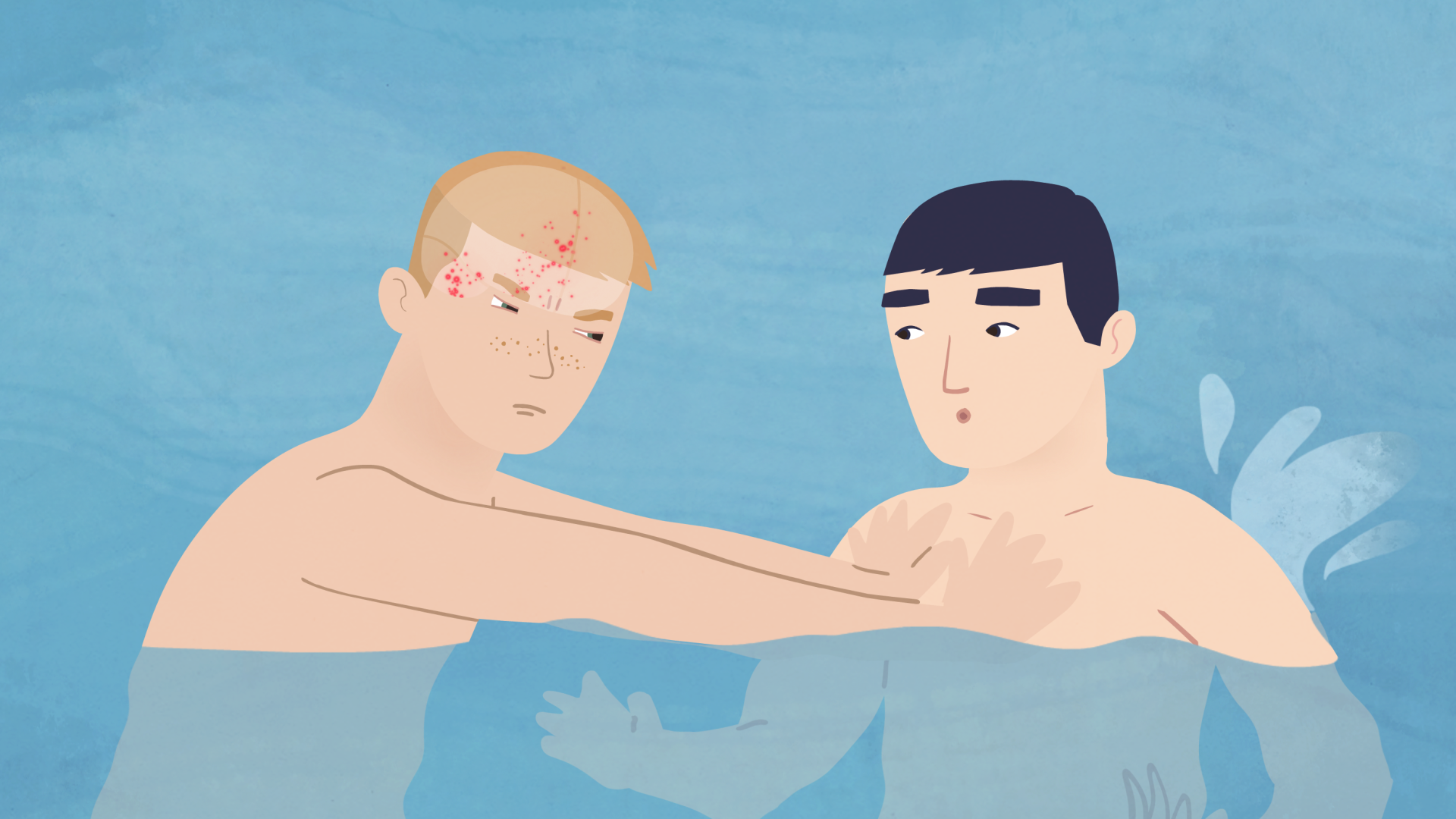

But abuse and neglect create a world where danger is often unpredictable and punishment is extreme. Researchers have shown that over time such experiences can lead to long-lasting changes in how the brain responds to danger, even in everyday environments. Scientists have observed heightened response in key threat regions of the brain, including the amygdala and the insula. This heightened response has been observed even when the threat is outside of conscious awareness. It is also similar to the pattern of response that has been seen in soldiers before and after they have been exposed to combat. This pattern of response is called hyper-vigilance and in the Childhood Trauma and the Brain animation, we saw John who frequently witnessed domestic abuse as a child. Heightened reactivity to threat can lead to overreaction and sometimes violence. When John overreacted to a playful nudge in the pool, the consequences had the potential to negatively impact his sense of self-worth as well as his network of friends and peers.

In some context, however, children — especially those with chronic experiences of abuse — show patterns of threat avoidance. This is associated with unusually low brain activation in the threat system. This may lead to a child withdrawing or feeling anxious even in safe environments and this could reduce their opportunities to learn and build relationships.

We know the changes in the threat system can impact how a child experiences everyday life increasing reactivity to stress and rejection. It may also reduce the amount of attentional resources that the child has for learning and paying attention, for example, in class. As we saw with John, it can also increase the intensity of emotion and emotional response and may be linked to poor emotion regulation. As we will see later, this can trigger more stressful experiences. Over time, scientists believe that changes in the threat system may increase vulnerability to later mental health problems such as anxiety and depression.

Scientists have also been interested in how abuse and neglect impact on the way that children respond to positive or rewarding aspects of their environment.

The reward system (3:27)

The reward system in the brain is what helps us learn about positive aspects of the world around us. it motivates our behaviour and guides decision making.

From the earliest years, our brain is able to learn what is rewarding and how to elicit rewards — a mother’s smile, a cuddle, as well as basic rewards such as food. Abuse and neglect create a world where these kind of rewards are inconsistent or even absent. Over time scientists believe that this may reduce the brain’s responsiveness to rewards. One suggestion is that this may help a child manage the likelihood of constant disappointment as they align their expectations to a world that shows them little care or attention.

The reward system comprises a range of brain areas, including the brain stem, the striatum, and frontal regions. These brain regions use dopamine an important chemical in the brain to communicate when processing reward cues.

Research shows the children like Jasmine have reduced sensitivity to reward in these regions compared to their peers. We believe that this may impact their ability to negotiate and maintain relationships. We know the changes in the reward system are also associated with problems learning about new rewards in the environment, including social rewards. There may also be an impact on the child’s motivation and their ability to experience pleasure.

Again, scientists believe the changes in the reward system following abuse and neglect may increase vulnerability to future mental health problems including anxiety and depression.

The memory system (5:21)

While we know quite a bit about the threat and reward systems, we are only just beginning to learn how early experiences can affect the memory system in the brain. The autobiographical memory system is important because it allows us to store information about past experiences. We need to access these past experiences to help us negotiate new challenges in the future. Our past memories are essential to help us plan, to problem-solve, and to make decisions. They also have a role in helping us regulate our emotions and, overtime, developing a sense of who we are.

Experiences of neglect and physical abuse create negative memories that may be overwhelming. We believe this might be one reason that contributes to changes in how a child’s brain processes memories in the future. We know that the autobiographical memory system is comprised of a network of brain regions, including the temporal and frontal areas. This includes the hippocampus, a key brain structure involved in storing memories.

Research shows us that children who experience trauma can develop a pattern of what we call overgeneral memory. Everyday memories become less detailed and we believe that this impacts a child’s ability to solve social problems, especially in new or challenging situations.

Brain imaging studies also suggest that everyday negative memories might also become more prominent than positive ones. This is seen in the brain as an increased activation of areas involved in negative memory recall, such as the amygdala. We’ve also seen decreased activation of the hippocampus when children recall positive memories. Scientists have suggested that the changes in the autobiographical memory system ultimately impacts a child’s ability to effectively negotiate their social world. They believe that the tendency to focus on negative memories and thoughts may also increase the risk of rumination. This may be particularly relevant during adolescence, a very formative period where we create our sense of self and our identity.

So, we briefly looked at evidence for how childhood trauma can impact the functioning of three different brain systems. It is important to note that many of these brain changes are observed even before mental health problems arise. That is, we see them in children with no obvious mental health disorder. This suggests that we have an important opportunity to take preventative action to reduce the likelihood that mental health problems will emerge at all. To do this, we need to understand how these brain changes increase latent vulnerability to future mental health problems.