Join the UKTC’s mailing list to be notified about our conferences and events, and new resources.

How latent vulnerability plays out over a child’s life

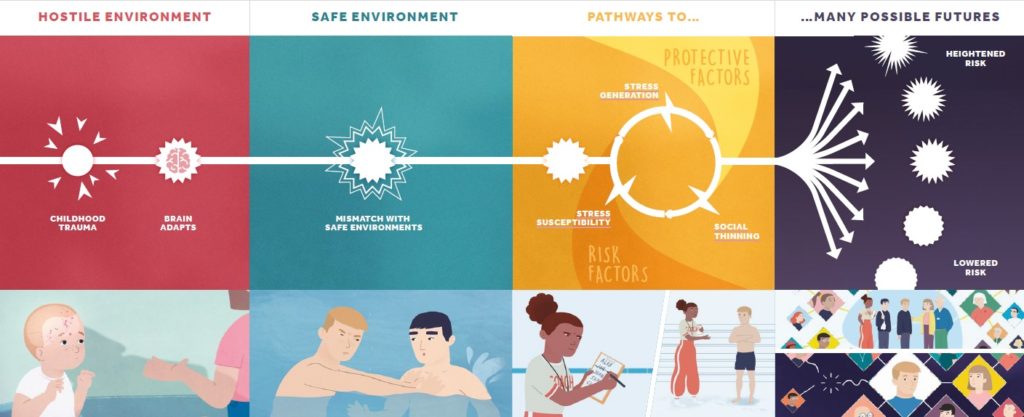

Latent Vulnerability infographic

Definition

The unseen link between childhood trauma and later mental health problems is called Latent Vulnerability. The word latent refers to something that exists but is not yet obvious, while the word vulnerability means more likely to be harmed. So Latent Vulnerability means that a child is at greater risk of harm than may be immediately obvious to carers or professionals.

While Latent Vulnerability is cause for concern, it does not determine anyone’s future. This infographic shows how the brain adapts and responds equally to new positive experiences from childhood into early adulthood and the many windows of opportunity to help children move onto a resilient path.

Full text of infographic

Emotionally and biologically, we are programmed to expect care and protection from our caregivers. When this fails to happen, a child – and their brain – adapts to cope. They may have to deal with a hostile external world to characterised by danger and neglect. They also have to manage an internal world, where emotions such as anxiety or fear can be overwhelming. Scientists have identified changes in the threat, reward and memory systems in the brains of these children.

Brain adaptations helpful in a neglectful or abusive home environment may not work so well in a safe environment, such as school or a foster placement. For example, they may lead a child to interpret an everyday interaction as hostile and make it harder to learn from new experiences. This can make conflict with peers more likely. Equally, social situations may seem more scary and confusing, making it harder to build and maintain relationships.

Latent Vulnerability is something that plays out over a child’s life in everyday situations at home and at school. In other words, it is a dynamic process. As adults we have a key role to play in enhancing the protective factors around a child. This includes supporting their social competencies, their relationships with peers and adults, and their access to new opportunities to grow and develop. It can be challenging, and takes patience and time.

Childhood experiences of abuse and neglect – has has been called ‘toxic stress’ – don’t determine a child’s future. Destiny is not fixed in early childhood. The brain adapts and responds equally to new positive experiences. Indeed, scientists have shown that our brain continues to mature and develop well into early adulthood. This means there are windows of opportunity for us to help children move onto a resilient path.